![]()

© 2015 -2025 Justin Constable, All Rights Reserved.

![]()

1. Introduction

Legal systems have long prioritized human-centric models of justice, often neglecting the rights and well-being of animals and the natural world. However, the interconnected crises of climate change, habitat loss, mass extinction, and social inequality reveal the urgent need for a broader rights-based paradigm.

This article argues that human, animal, and nature rights are not isolated but interdependent. It further contends that these rights must be enshrined in a legal framework grounded in the rule of law, enforced through a strong separation of powers, and guided by both historical precedent and contemporary statutory instruments such as the Care Act 2014 and the Housing Act 1998.

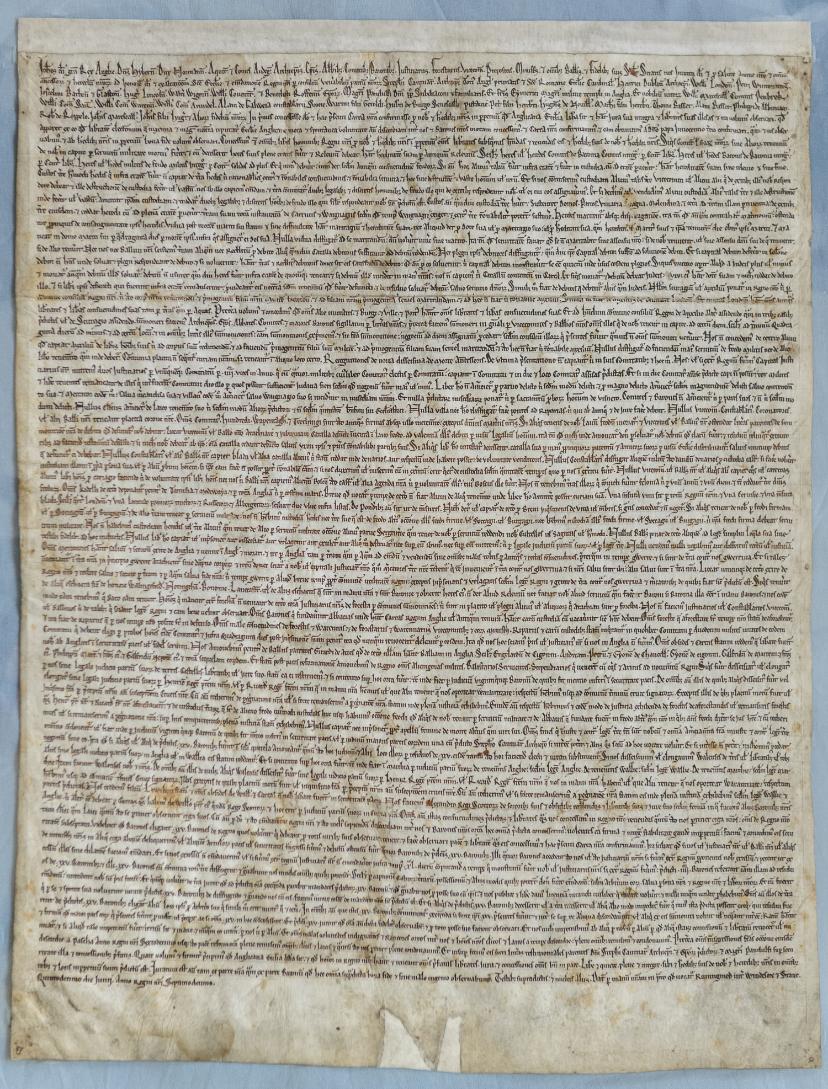

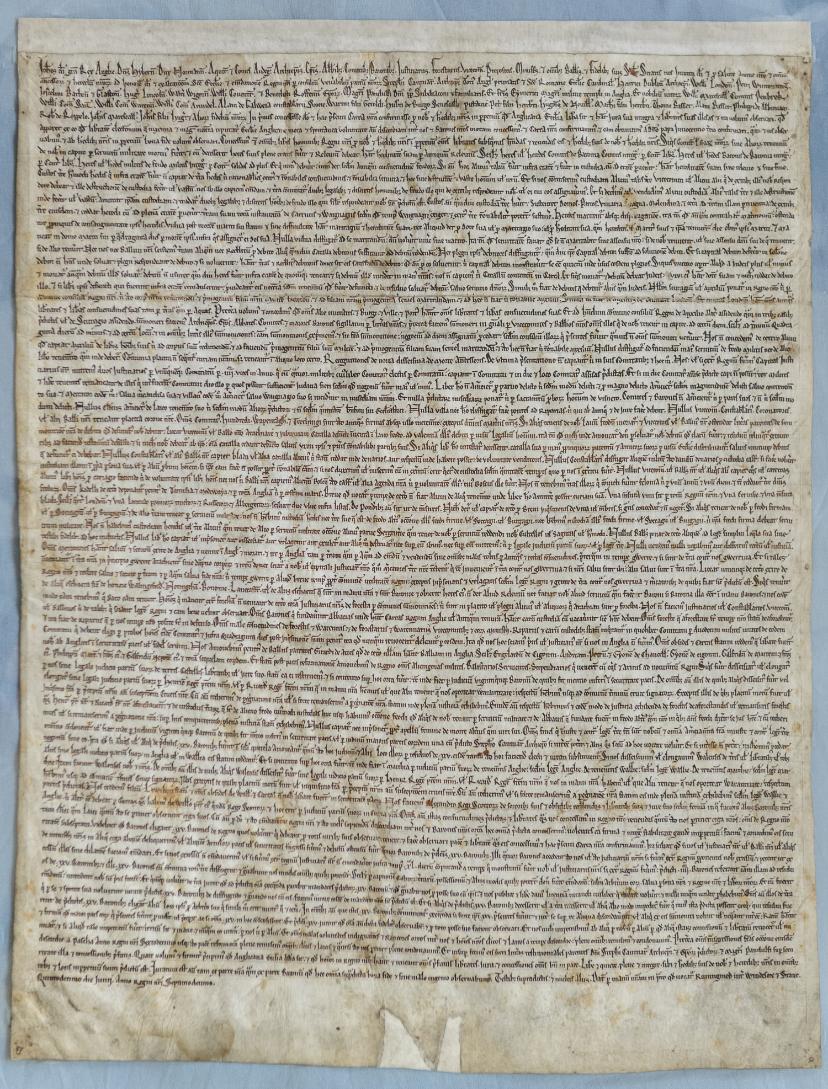

2. The Magna Carta and the Origins of Legal Accountability

The Magna Carta, sealed in 1215, is widely regarded as the origin of modern legal accountability. It institutionalized the principle that rulers are not above the law. Clause 39—“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned... except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land”—established the foundation of due process and legal equality (Vincent, 2012).

This commitment to law as a safeguard against tyranny underpins democratic governance and human rights protections today. However, the scope of this protection must now be extended. If the law is truly to serve justice, it must evolve to defend not only individuals, but the ecosystems and species on which life depends.

3. The Separation of Powers: A Framework for Justice

The separation of powers, most famously theorized by Montesquieu and later embedded in constitutions worldwide, divides authority among legislative, executive, and judicial branches. This structure prevents the concentration of power and ensures independent enforcement of laws and rights (Vile, 1998).

A functioning separation of powers is critical to extending rights protections to animals and ecosystems. Without it, environmental legislation and welfare protections are vulnerable to political interference and industry lobbying. Effective checks and balances are essential to implement and enforce an integrated rights framework.

4. Human Rights and Social Protections in Law

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) enshrines the inherent dignity and equal rights of all people. Building on this, national statutes like the Care Act 2014 and Housing Act 1998 bring rights into practical governance:

The Care Act 2014 is a piece of UK legislation that reformed how social care is provided to adults in England. It aims to create a more consistent and person-centered approach to care and support, and also includes provisions for safeguarding adults from abuse or neglect.

Key aspects of the Care Act 2014:

Adults with Care Needs:

The act focuses on the care and support of adults with care needs, including older people, and how these needs are met and paid for.

Local Authority Responsibilities:

It outlines the general responsibilities of local authorities in providing care and support, including assessments, information, and advice.

Safeguarding Adults:

The act places a statutory duty on local authorities to safeguard adults from abuse and neglect.

Personalization and Participation:

It emphasizes the importance of involving individuals in decisions about their care and support, ensuring their well-being and independence.

Eligibility Criteria:

The act establishes clear eligibility criteria for accessing care and support services.

Charging and Financial Assessment:

It also addresses how individuals contribute financially to their care and support.

.

The Housing Act 1998 refers to both Irish & British legislation.

In Ireland:

In the UK:

These Acts make tangible the promise of civil liberties by embedding protections into statutory obligations. Yet these protections stop at the boundaries of the human species—and fail to consider the environmental systems on which housing and care depend.

5. Animal Rights and the Expansion of Legal Standing

Animal rights have long existed in philosophical debate but are only recently entering the legal mainstream. Peter Singer’s (1975) principle of equal consideration of interests challenges species-based discrimination, while Steven Wise (2000) advocates for legal personhood for cognitively complex animals.

Progressive legal systems are beginning to respond. In 2020, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court ruled that a woolly monkey named Estrellita had rights under the nation’s constitution, which recognizes nature as a subject of rights (González, 2022). The court emphasized the state’s duty to prevent suffering, recognizing the animal as a rights-bearing subject.

This shift from animals as property to beings with legal interests marks a pivotal moment. Like human rights, animal rights must be integrated into law through enforceable mechanisms, protected by the same institutional safeguards.

6. Nature Rights and Legal Personhood of the Environment

The Rights of Nature movement argues that natural entities—rivers, forests, ecosystems—deserve legal personhood and the right to thrive. Countries like Ecuador and Bolivia have amended their constitutions to reflect this view, while New Zealand recognized the Whanganui River as a legal person in 2017, with appointed guardians to represent its interests (Ruru, 2018).

Earth jurisprudence, pioneered by thinkers such as Thomas Berry (1999) and Cormac Cullinan (2011), posits that law must evolve beyond anthropocentrism. This jurisprudence aligns with environmental ethics and the rule of law by ensuring that ecosystems are protected not only for their utility, but for their inherent value and continued existence.

7. Integrating Rights: A Unified Legal Framework

A future-proof legal system must integrate:

Human Rights & Civil Liberties – Grounded in dignity, procedural fairness, care, and housing security.

Animal Rights – Recognizing sentience, autonomy, and the right to live free from cruelty or exploitation.

Nature Rights – Including rights to regeneration, balance, and protection from degradation.

Rule of Law – Ensuring consistency, fairness, and access to justice for all beings.

Separation of Powers – Guaranteeing institutional integrity and independent enforcement.

This integration is not merely theoretical. It has practical implications for policy, governance, infrastructure, economics, and social services. Models such as Doughnut Economics (Raworth, 2017) and Earth Law provide pathways for implementation, linking ecological limits to social foundations.

8. Conclusion

The Magna Carta laid the groundwork for civil liberties and lawful governance over 800 years ago. Today, that same vision of justice must expand to encompass animals and nature. Statutes like the Care Act 2014 and Housing Act 1998 show that human needs can be protected through law—but to survive and thrive as a species, we must extend those protections outward.

A legal system that protects life—human, animal, and ecological—is the only just and sustainable future. Such a system must be codified in law, enforced through the separation of powers, and accessible to all under the principles of the rule of law.

Berry, T. (1999). The Great Work: Our Way into the Future. Bell Tower.

Cullinan, C. (2011). Wild Law: A Manifesto for Earth Justice (2nd ed.). Chelsea Green Publishing.

Donahue, C. (2003). The Medieval Constitution: Magna Carta and the Emergence of the Rule of Law. Yale Law Journal, 112(8), 2137–2178.

González, J. (2022). Ecuador’s Animal Rights Case: A Landmark for Earth Jurisprudence. Environmental Law Review, 24(1), 5–14.

Koivurova, T. (2008). Human Rights Approaches to Climate Change: The Challenges of Human Rights Protection in the Context of Climate Change. UN Chronicle, 45(1), 22–25.

Linebaugh, P. (2008). The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All. University of California Press.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Ruru, J. (2018). Listening to Papatuanuku: A Call to Reform Water Law. Journal of Environmental Law, 30(1), 1–10.

Singer, P. (1975). Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals. HarperCollins.

Government of Ireland. (1998) The Housing (Traveller Accommodation) Act 1998

UK Parliament. (1998). Housing Act 1998. https://www.legislation.gov.uk

UK Parliament. (2014). Care Act 2014. https://www.legislation.gov.uk

Vincent, N. (2012). Magna Carta: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Vile, M. J. C. (1998). Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers. Liberty Fund.

Wise, S. M. (2000). Rattling the Cage: Toward Legal Rights for Animals. Perseus Books.

Legal Preamble

Human, Animal, and Nature Rights Under the Rule of Law and the Legacy of the Magna Carta form part of the Terms of Use for all The Liberty System's interfaces, services, and programs. Violations may result in limited access, removal from the system, or lawful accountability where applicable.

Adherence to these laws enables protection of service users, providers, and the integrity of the Project 369 ecosystem.

© 2015 -2025 Justin Constable, All Rights Reserved.

![]()

The Magna Carta was not written by a single individual, but rather drafted by a group of barons and church leaders in 1215, with the help of royal clerks, under pressure from King John of England.

The key contributors were:

The rebellious English barons, who demanded limits on the king's power.

Archbishop Stephen Langton, who played a central mediating role and likely influenced much of the document's language.

Royal scribes, who formalized the clauses and structure into Latin.

King John sealed the Magna Carta at Runnymede on June 15, 1215, not out of goodwill, but to avoid civil war. He later attempted to annul it, which led to further conflict.

While no single person "authored" the Magna Carta, it was collectively created through negotiation between the monarchy and the feudal elite, with heavy influence from the Church.

The Magna Carta is considered a protected and historically significant document,

though not in the way modern statutes are "protected" under law.

Surviving original copies of the 1215 Magna Carta are held by institutions like:

The British Library (which holds two of the four surviving originals),

Lincoln Cathedral (now at Lincoln Castle),

Salisbury Cathedral.

These are preserved in climate-controlled vaults and protected as national treasures in the UK.

Most of the clauses of the original 1215 Magna Carta were annulled within months by Pope Innocent III, under pressure from King John.

Later versions were reissued in 1216, 1217, 1225, and 1297 (under Edward I), with revisions.

Only a few clauses remain on the UK statute books, particularly:

Clause 1: Freedom of the Church of England.

Clause 13: Liberties of the City of London and other boroughs.

Clause 39: Due process and legal judgment (“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned…”).

These remaining clauses are still part of UK common law and symbolically referenced in legal arguments about liberty, justice, and the rule of law.

The Magna Carta is considered a foundational document for constitutional government and human rights, influencing:

The U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

It's principles—especially rule of law, limits on arbitrary power, and access to justice—are widely cited in international legal theory, though the document itself is not enforced outside the UK.

It's protected historically and symbolically, and small parts still have legal force in the UK.

It's greatest influence is philosophical and constitutional, not statutory.

As of today, only three clauses of the Magna Carta (1297 version) remain in force under English law. These were confirmed by Parliament in the Statute of 1297 under King Edward I, which incorporated parts of the original 1215 Magna Carta into statutory law.

Here are the three surviving clauses still in force:

"The English Church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished and its liberties unimpaired..."

Guarantees the independence of the Church from state control.

Still cited symbolically today, though its practical application is limited due to the modern relationship between church and state.

"The City of London shall have all its ancient liberties and free customs..."

Protects the historic rights and privileges of the City of London and extends similar liberties to other cities and towns.

Still referenced in debates about local government powers and historic charters.

"No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions... except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land."

"To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice."

This is the most famous and enduring clause, forming the foundation of due process and the rule of law in the UK and many democracies.

Still legally binding and regularly cited in court cases.

The rest of the 60+ original clauses—many dealing with feudal customs, debts, and baronial privileges—were repealed over time or became obsolete.

Statute of Magna Carta 1297 (25 Edw. 1), available through UK legislation archives:

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/aep/Edw1cc/25/9

![]()

Make a free website with Yola